It didn’t look Tudor at all. I walked past two or three times thinking this couldn’t be right, but then decided this must be the Sutton House I had come to see. Half of it was rendered, the forecourt was paved, the windows were clearly eighteenth century, there was a 1930s noticeboard about its acquisition by the National Trust, and the only clue to a Tudor past was one of the two front doors. Inside, the house was both grubby and tatty. There were people handing out leaflets, a serious-looking lady dispensing tea and cake, and, in the courtyard, a bearded man waving his arms and exhorting a small group of followers about maps.

It was a close-run thing. It would have been easier to accept a leaflet, drink a hasty cup of tea and leave. But I didn’t. And I was one of the people who ended up fighting for a better future for for this bedraggled survivor of five centuries of change. It nearly didn’t make it, threatened, by the late 1980s, not with demolition but with gentrification. When the house was new, in the 1530s, it was part of a semi-rural community where residents built second homes away from the pressures of the City three miles away. Ralph Sadleir, a young man on his way up in the world, had managed, still in his twenties, to fund a new brick-built house for his young family.

But none of us knew that then. At the time of the Save Sutton House campaign it was still accepted that this was once the home of Sir Thomas Sutton. Or maybe Sir Julius Caesar. And possibly involving one of several semi-Royal Hackney residents, always supposing we have eliminated the assorted hangers-on of Christopher Urswick, Rector of Hackney, once the almoner of Margaret Beaufort and latterly the centre of what he would hate to be remembered as a group of reformers. But we know that Desiderius Erasmus, famed theologian, was also famed as a freeloader, and tracked Urswick down to Hackney in search of the price of a new horse, but Urswick then in his 70s, was out hunting, and so not available for cadging. But that’s a very old story.

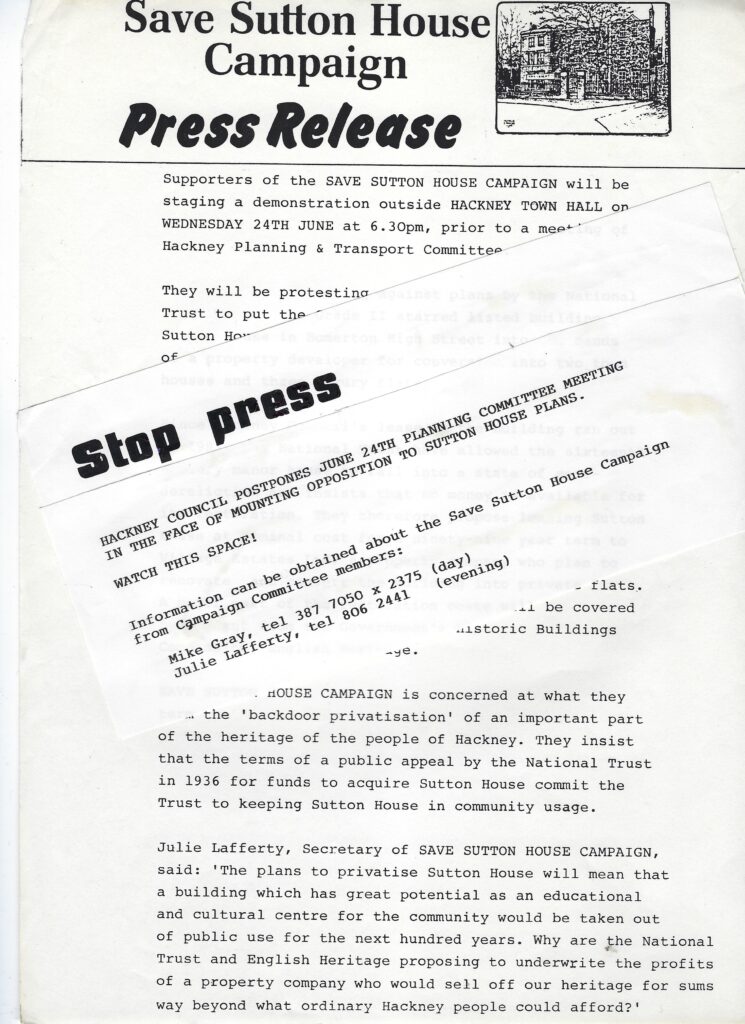

It took months of campaigning, several petitions and a lot of publicity to persuade the National Trust they were not going to get away with allowing this unloved property to be turned into five luxury flats that would then be open to the public only once a year. The local authority had been approached with the suggestion that Sutton House should become a museum, but councillors had responded that it would be better if this piece of “built imperialism” were to be “razed to the ground”. The National Trust and its chosen developer had then gone ahead with making a planning application for the flats scheme, and this got as far as a listing in the Hackney Gazette. It was seeing this that persuaded some half-dozen local residents first to respond to and then to resist the plans.

So it was that the Save Sutton House campaign was born. From fairly chaotic beginnings, the outline of a plan to restore and open the house for community use came into being. By late 1987 there was enough common ground between the campaigners and the National Trust to allow a jointly organised open day to take place. Such was the level of local interest that, in response to a publicity effort that largely consisted of A5 black and white posters attached to trees, some 800 people visited. And this was just the beginning.

Over the next few months it was agreed that Sutton House should be restored, the work to be paid for from grant funding, and the house then made available for a variety of education, arts and commercial uses, the historic rooms to be open to visitors for some of the week, a café bar opened, and the whole scheme to be jointly managed by the National Trust and the Sutton House Society, presided over by a Local Committee elected by both organisations. A project manager and fundraiser were appointed, along with an architect. A structure of sub-committees was agreed upon, with the membership of each drawn from both organisations. The restoration was to take place in two phases, to be completed by early 1994.

It is hard to over-state how radical this scheme was at the time of its inception. In the last decade of the twentieth century, the word Hackney still spelled decay to much of the world. Books with titles involving the word “ruins” set out the perceived awfulness, poverty and hopelessness of the East End in general and Hackney in particular. If anyone from what was then still Fleet Street wanted an example of urban decay, all too often a reporter and a photographer would venture up the City Road and make sure they found what they were looking for. As to the National Trust, many of its senior employees were tentative about visiting Hackney, and its was only a few years since James Lees-Milne had recorded his distaste for both the property and its surroundings. One memory of this time involves three of them emerging from Sutton House, with one asking the others “where d’you get lunch this side of the Limpopo?”. We all had a lot to learn.