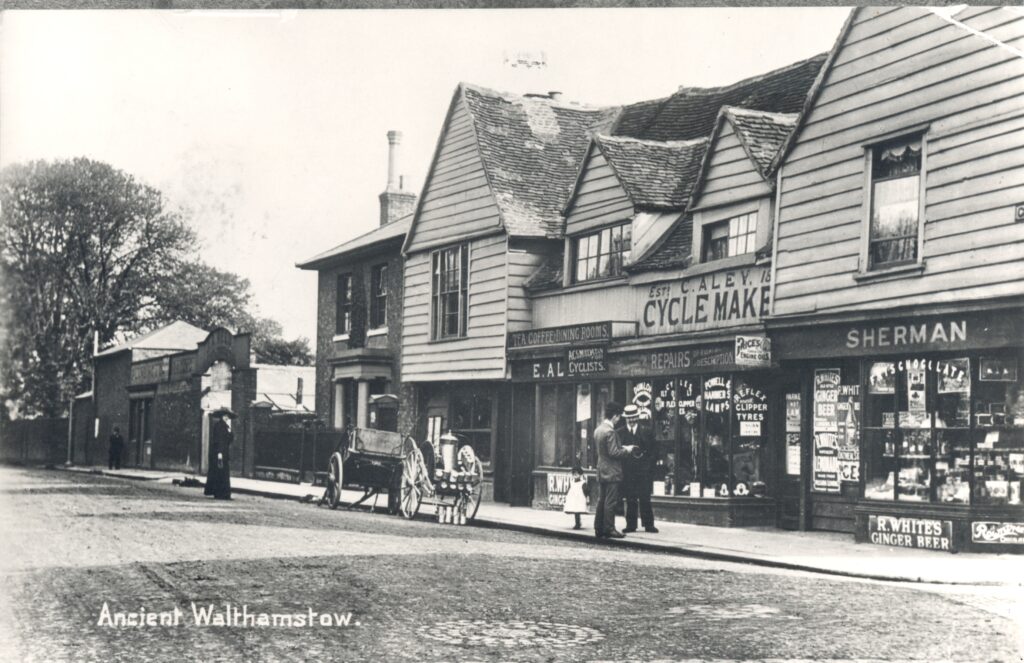

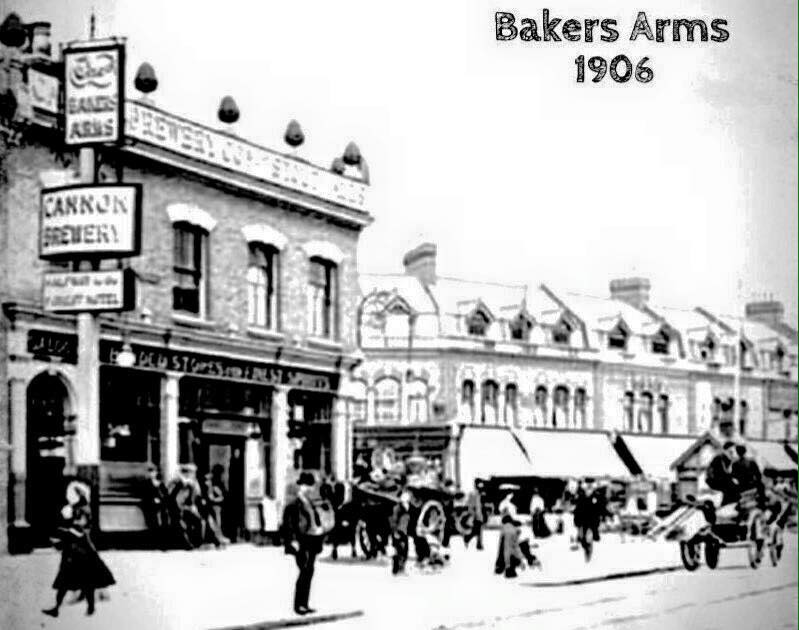

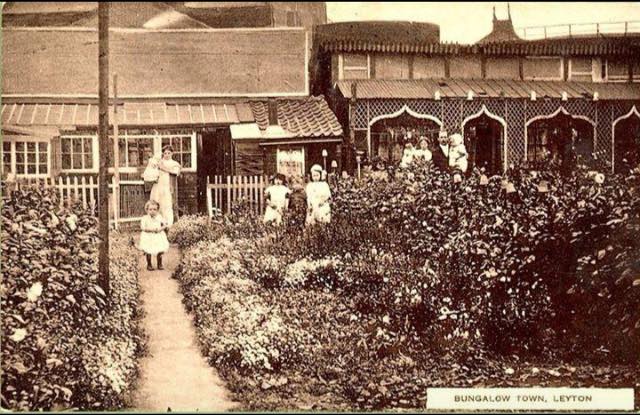

From damp orchards and watercress beds to a hodge-podge of terraced housing, shops and small factories and workshops was a short journey for an inoffensive field in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. For the area between Boundary Road to the south and what is now Walthamstow High Street to the north, the transformation was especially easy as former common land and once-grand gardens went on the market. And some of what was built survived only a few years, vanishing to make way for higher bidders.

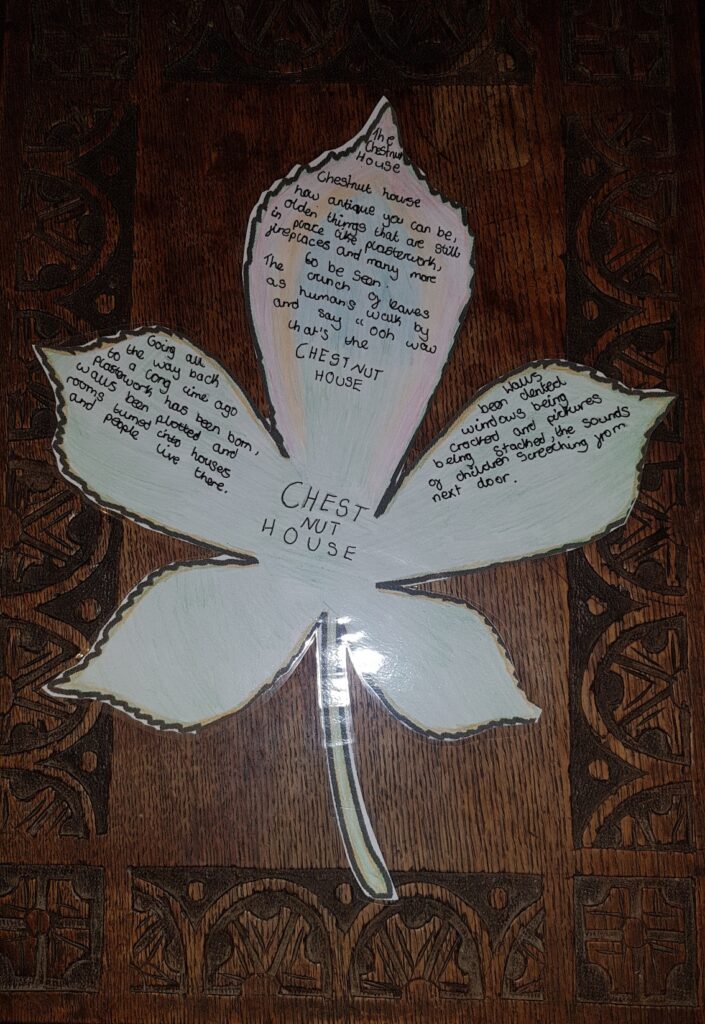

But there are a few places and buildings that have survived unexpectedly, sometimes against the odds. One of these is a smallish and outwardly unprepossessing structure, now dignified with the title of “Stafford Hall”. It has been in turn scout hut, dance hall, a school for “mentally handicapped boys”, cinema and photography club, occasional performance space and pop-up pub. But first of all it was a church.

Iron churches were not unusual at the turn of the twentieth century; this one was bought second hand for £40 from Battersea, and cost an additional £70 to move and reconstruct. The plot of land that accommodates it as well as St Barnabas Church next door and its vicarage had been donated by H J Casey, city businessman, property developer and owner of The Priory, a grand house in Forest Road. This was a usual piece of philanthropy at the time – Casey, like many others who were making a second fortune from land, might give away a small patch of their profit to provide the ground for a church for the occupants of the hundreds of new houses. Commercial premises were automatically part of the plan. But churches costed – it was a piece of good luck for this relatively poor area that there was a millionaire philanthropist down the road.

In fact, though, the first ancestor of St Barnabas church was the parlour of Mrs Elizabeth Tracey of Stafford (now St Barnabas) Road. The Traceys’ must have been a busy place in the 1890s, as only was it home to Elizabeth, her husband Matthew, an iron moulder and children but the living room in their small house was often used for choir rehearsals, prayer meetings and a Sunday school. Heartbreakingly but not unusually, Elizabeth had borne ten children, of whom only five survived to adulthood – and this was a moderately prosperous family.

But at the end of the decade the Traceys got their house back. The original plan had been to use the plot opposite as a mission church, as was often done in the case of newly built-up areas. Before the 1870s, the nearest church was St Mary’s, a good twenty-minute walk away, mostly across fields in the days before Queen’s Road was laid out to allow access to the new cemetery, opened in 1872. And, contrary to some assumptions about nineteenth century history, by no means everyone went to any kind of religious service as a matter of routine, and certainly not if it meant two longish walks

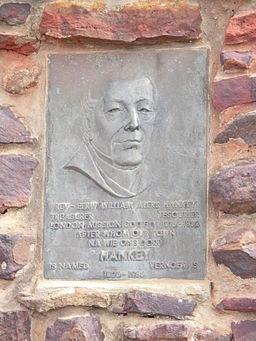

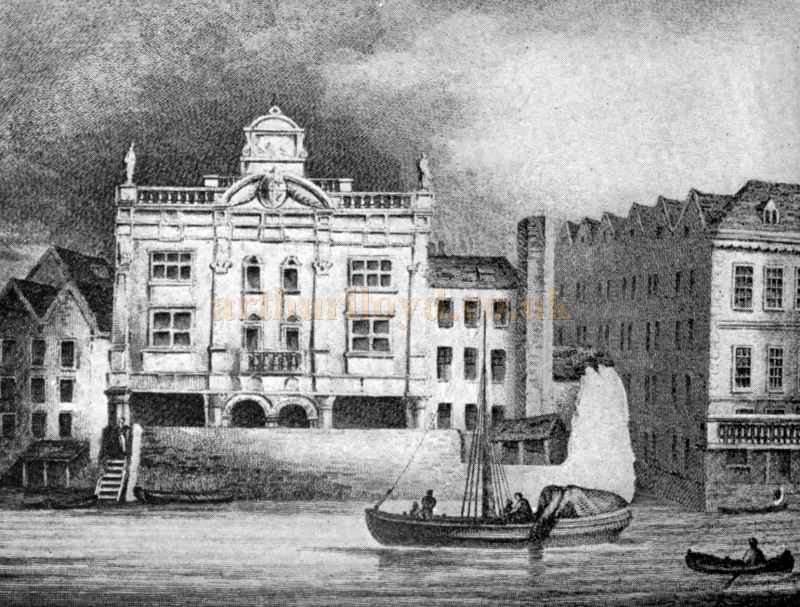

Markhouse Road, or rather Lane, was to become the setting of a large and impressive church largely because of the chance of inheritance. Richard Foster was a City merchant and devout Anglican, and was the heir of his uncle, James Foster, who had lived in a house in Markhouse Lane since the 1830s. On his death he left much of his estate to Richard, who offered some of the land to the Church of England. This was the plot that was to become St Saviour’s, built at Foster’s expense. The architect was T F Dolman, whose design was in the thirteenth century style of the height of the Gothic Revival. Over the next thirty years, Foster was to spend the equivalent of several million pounds on building churches both in Walthamstow and other newly expanding suburbs.

St Barnabas Church was to be Foster’s final church building project. The “Iron Church” was in operation by 1900 – it was realised at the last moment that there was no font, so the newly appointed churchwarden, a mason by trade, made a wooden font overnight. It was then consecrated by the Bishop of St Albans, and remained in use until the permanent structure was ready. Foster took part in a ceremony to “cut the first sod”; there was a lunch afterwards in the iron church. In his speech, Foster said this last project was a thank offering for a life which had held many blessings. He was to live to see the permanent church completed, but made only a modest contribution towards the hall that is named after him.

So the iron church went on serving as the parish hall for fifteen years after St Barnabas’ Church was completed and the large and elegant vicarage made ready for its first occupants. This was, and is, the grandest house in the neighbourhood, which was a relatively poor one. Rather ironically, one of the first parish magazines, dated February 1905, reports that soup had been made at the Vicarage for the benefit of those who were suffering from “slackness of work”. It was, however, sold for 1d per quart. The recipe is not given.

In recent years the name of Stafford Hall seems to have become official. There have been several very popular pop up pubs there, and at the time of writing it is, after a coat or two of paint and the addition of several sofas, seeing service as a warming room.