A time traveller going back five centuries would be likely to get lost In Walthamstow. St Mary’s Church is in the right place, but is a different shape, inside and out. The Ancient House is more reliable, but lacks a wing, is weatherboarded and surrounded by farmland. Hoe Street is there, without a single chicken shop, and fringed with substantial houses set back from the road.

This was a desirable place to live, with good farmland, but within easy reach of London. In the 1520s there were 99 taxpayers, which probably indicates a population of about 400. And by the sixteenth century Walthamstow was home to a number of City merchants. One of the most influential was Sir George Monoux, a draper and former Lord Mayor London who bought a large house and estate just outside Walthamstow. He was generous to his new community, founding a school and almshouses and paying to have the parish church virtually rebuilt.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century London was not in the first division of European cities. With a population of around 30,000, it was dwarfed by not only Paris, which was perhaps seven times bigger, but Milan, Venice, Florence and Naples. This applied, too, to the economy, battered by civil war, and to English culture, as there had been less money or resources to spare for art and building.

Early Tudor London was hardly bigger than the present-day City, covering just about a square mile. Tower Hamlets were indeed hamlets, there was some small scale development south of the river at Southwark, and Westminster remained a separate city, reached via the Strand, although this was lined with grand houses belonging to an assortment of nobility and bishops. But Henry VIII was determined to raise the status of his capital city, and of his court. When he was crowned king in 1509, he was a cultured, athletic and ambitious eighteen year old – and the royal exchequer was healthy after a quarter of a century of Henry VII’s enthusiastic tax gathering. And the new king was happy to take the credit for the building and cultural work his father had begun.

So the young Henry VIII, inheriting a full exchequer, began a programme of enthusiastic spending – on building new palaces and on improving those he had, on defence, especially ship building, and on surrounding himself with the best artists, artisans, designers and musicians to be found, anywhere. King Henry’s ambassadors and agents soon began to recommend talented makers who might adorn the English court. And ambitious people from all over Europe began to think of London as a place to make their career and their fortune. The painter Hans Holbein was to be one of these.

Venice was one of the independent states that made up sixteenth century Italy. It also had its own overseas possessions, including Crete, and had for centuries been a centre for international trade. The city had a diverse and international population as a result of all this. Although its political influence was beginning to wane, it remained one of the great European centres for all the arts.

The Bassano family had appeared in Venice in the late fifteenth century. The surname they finally took was that of the village in the Veneto where they lived for a while, probably making a living by trading in silk. There is some evidence that the family was of Jewish origin, moving from Sardinia or Portugal when Jews became unwelcome there.

Sometime in the early 1530s the Bassanos were approached by one of Henry VIII’s agents about the possibility of moving to London, and four of the brothers, Alvise, Anthony, Jasper and John, were invited to England to play for the King. They stayed for about a year, playing in one of the bands that were employed at court, on standby to play for Royal guests, but then returning to Venice. But in 1538 all six of the younger generation of the family moved to London, bringing with them their whole stock of instruments, and taking permanent court appointments. The grandfather of the family became known by the surname “Piva”, meaning “bagpipe”. And at some point the Bassanos moved from silk to music, with some success, as they obtained a place at the court of Venice’s ruling doge, where they both played and made musical instruments. The memory of the silk was kept alive by the maker’s mark they chose for the instruments they made: two silk moths.

Sometime in the early 1530s the Bassanos were approached by one of Henry VIII’s agents about the possibility of moving to London, and four of the brothers, Alvise, Anthony, Jasper and John, were invited to England to play for the King. They stayed for about a year, playing in one of the bands that were employed at court, on standby to play for Royal guests, but then returning to Venice. But in 1538 all six of the younger generation of the family moved to London, bringing with them their whole stock of instruments, and taking permanent court appointments.

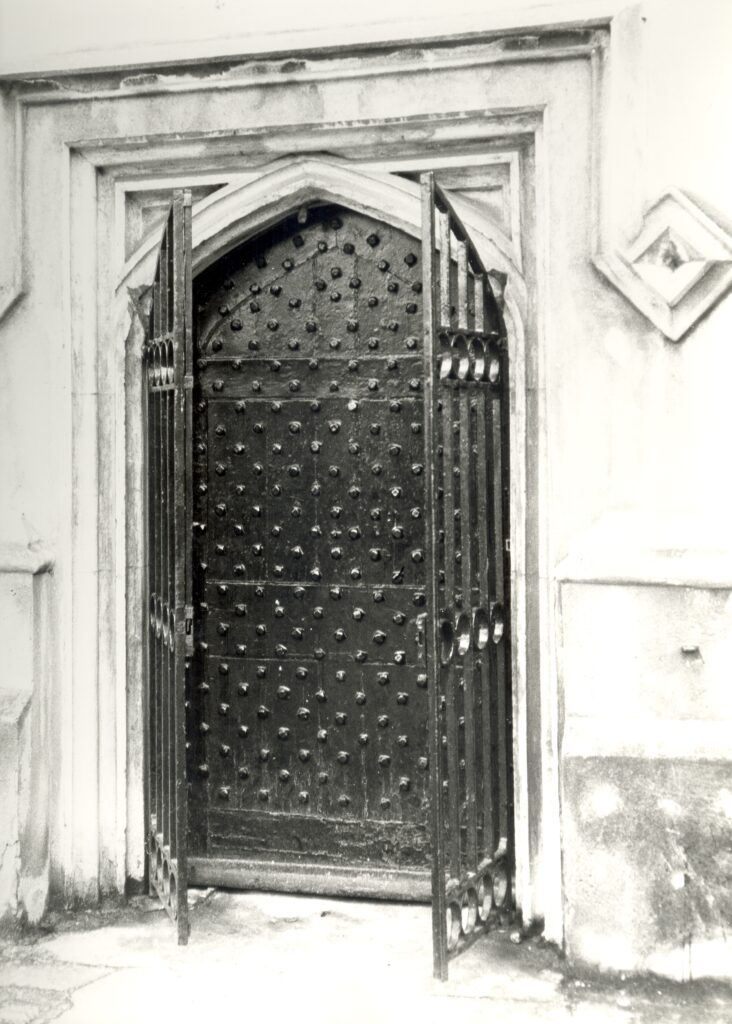

The Bassanos also found premises, first in the former monastic buildings at the Charterhouse, then in Mark Lane near the Tower of London where they set up a musical instrument making business. Like almost all Londoners of their time, they were churchgoers: their names appear on the records of All Hallows by the Tower, where members of several generations of the family were to be buried. A plaque to one of them is still in place.

And once they were settled and prosperous enough, the Bassanos began to buy property away from, but within reach of, the City. Walthamstow, with its good communications and rich farmland, was not a surprising choice. The first Bassano house here, on what is now Walthamstow High Street, was called The Starlings – as time went on other members of the family bought houses and property locally. It is likely that, like other City people, they commuted here for peaceful weekends and holidays away from the noise and dirt, and that their children lived here full time.

In early Tudor times most music was played, sung and listened to in private houses and churches. Not only was there no recorded music – there were no public concert halls, and public theatres only began to appear later in the century. For most people, if they wanted music they would play and sing it themselves. Any educated person was expected to be able to sing, dance and, preferably, be competent on one or more musical instruments. This was especially important for anyone hoping to get a job in a grand household (and this was the usual way up in the world). Students going to university or law school were often provided with musical instruments as part of the equipment they took with them.

Musical instruments were prized items, and the Bassanos were clearly skilled and adaptable makers. An inventory of a wooden chest of instruments for sale lists over a dozen different kinds of wind instrument, and there are other references to stringed instruments such as an inlaid ebony lute. The Bassanos, like other makers, signed the instruments they made, in their case with two silk moths. Probably in reference to their silk-dealing past. And these instruments often sold for high prices – Sir William Petre of Ingatestone Hall paid nearly £1 for a lute for his son – this at a time when £5 a year was a decent income.

The six brothers all had children of their own; many of them became musicians and instrument makers – there were Bassano musicians at court until at least 1630, and over the intervening years most of the sovereign’s musicians were family members or part of their circle. The name of one of the second generation, Emilia Bassano, later Lanier, has recently become famous as there is evidence she may have been Shakespeare’s Dark Lady of the Sonnets. And it is now claimed that this exquisite miniature by Nicholas Hilliard is of her – certainly the sitter has silk moths, the mark of the Bassanos, embroidered on her bodice.

There were Bassanos in Walthamstow and nearby at Waltham Abbey for at least a hundred years – one of them had to pay extra tax in 1615 instead of helping to maintain local roads. And in London, there were Bassanos living at their house in Mark Lane until at least the 1640s. There were a number of families of Italian descent in the area.

In the nineteenth century the name Bassano again became famous when Alexander Bassano became a fashionable photographer specialising in rehearsal shots of theatre productions – this one is from a “Henry VIII” of the 1890s. In the 1960s Bassano and Vandyk were well known society photographers – and there are Bassano musicians in London today. As to their instruments, only a few years ago a Bassano recorder, complete with silk moth logo, was found for sale in a market – still in a playable state.