At the turn of the nineteenth century, Hoe Street was still a well kept suburban road. The houses along each side were spacious, so were the gardens – these were on a less grand scale than country houses in the shires, but needed perhaps half a dozen indoor servants to run, with gardeners, grooms and coachmen too. This was the leafiest of suburbs.

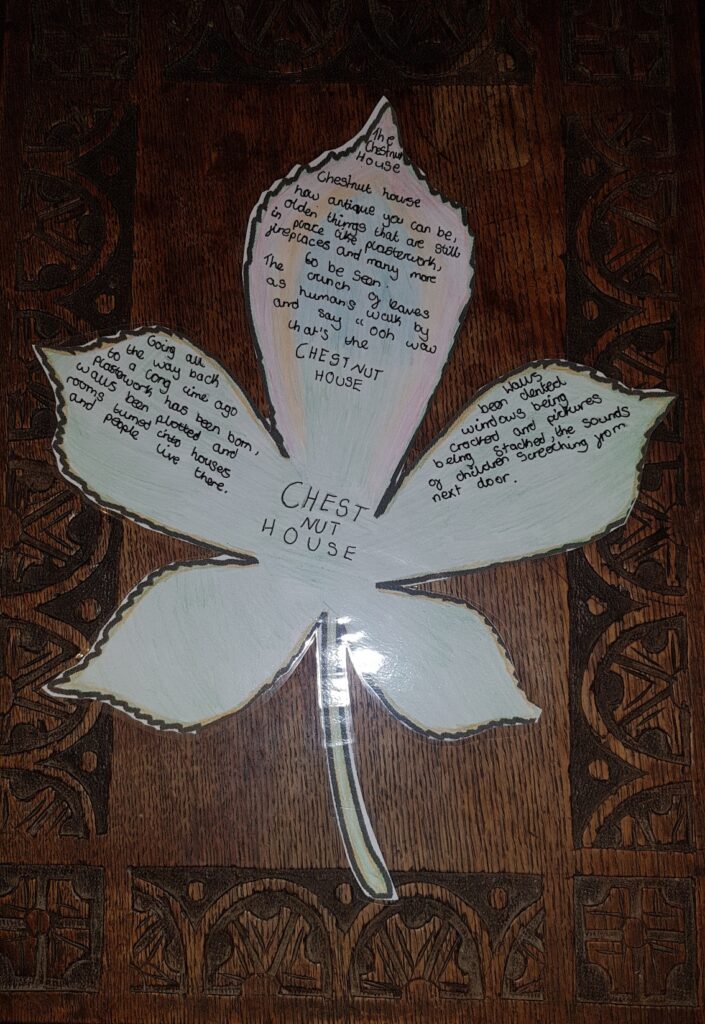

Hoe Street was home to people on their way up or down in the world, usually as they made or lost a fortune in the City. This was certainly true of The Chestnuts in the late eighteen and early nineteenth centuries. Many residents only stayed a few years, often moving on to a grander, more permanent home – if their luck in the games of City snakes and ladders held good. In some cases, little is known what later became of them. The house they lived in remains, in many respects, little changed.

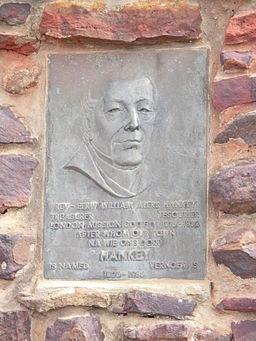

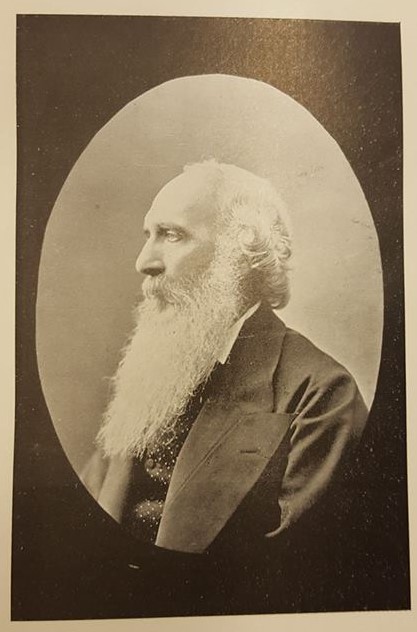

One of the better documented is William Alers Hankey, much respected in his time, but whose memory is less than comfortable for some. Born in 1771, the son of Thomas Hankey and a Miss Alers who was probably the governess in his household, Hankey was educated at the University of Edinburgh, returning to London to enter his father’s bank. He was evidently a successful businessman, and gained his father’s esteem to the point of being allowed to add the surname Hankey to his original name of William Alers. He lived first in Hackney, later taking on the tenancy of The Chestnuts. He had married Maria Martin, the daughter of a colleague, and he settled down to being a domestic tyrant, requiring his daughters to address him as “Mr Papa”. Hankey was instrumental in the missionary society movement, and a co-founder of the Foreign Bible Society – there is a town named after him in the East Cape.

Hankey was among those who claimed to support the abolition of slavery. He appeared before a Commons Select Committee maintaining that he wanted to free the 300 slaves he owned on the Jamaica sugar plantation his company had acquired via a mortgage default. However, he considered that preparation was needed because the condition of enslavement was degrading so enslaved people needed religious instruction before they were fit to deal with freedom. He had bought and sold slaves as late as the 1820s. When compensation was allocated in 1837, Hankey’s share was £5,777 8s 0d (the equivalent of at least £1.5M today). He died, aged 88, worth £250,000 – multiply by at least 150 for modern values: a multi-millionaire.

Hankey’s successor at The Chestnuts was another City merchant, but a very different character. Mr Powell, a merchant of Mincing Lane moved his family into the Chestnuts in 1854. Among his children brought up there was his son, Frederick, a delicate boy whose life was often despaired of. But he lived to grow up, studying Anglo Saxon at Oxford, later becoming Regius Professor of Modern History and helping to found Ruskin College. He described himself as a “socialist and a jingo” politically, and a “decent heathen Aryan” in terms of religion.

The last family to live in The Chestnuts were the Reads. John Read had been born in Jamaica, the child of relatively poor parents – his father was working in a clerical job. He was sent home aged only four months to live with his grandparents in Woolwich – the young John went on to become a successful stockbroker, putting aside his musical ambitions until he had made enough money to marry and then to settle his wife and six children in a substantial house in Walthamstow, first in Marsh (now High) Street, then moving to the Chestnuts, where they were to stay over twenty years.

J F H Read, as he was usually known, became noted in the area, where he served as a JP, as a supporter of many charities, as the Chair of the Schools Board and in church circles – he was a church warden of the then newly built St Saviour’s Church. Now with time to spare to devote to his music, Read played the viola in the Stock Exchange orchestra, and began to compose music; many of his pieces were played by the orchestra of the Walthamstow Musical Society. Lacking a venue big enough for his orchestral pieces, Read put up the money to build the Victoria Theatre in Hoe Street – it occupied the area where the Granada cinema now stands. Read was also churchwarden at the newly built St Saviour’s Church, and wrote many pieces to be played on the organ there.

In the time it was the home of the Read family, The Chestnuts was run on comfortable lines, with a domestic staff including a cook, two housemaids, a general servant, a coachman and a stable keeper as well as a governess and nursemaid listed in the 1881 census. Two of the sons were away, presumably at school, on census night, but four of the Read children were at home. This was a house with twelve main bedrooms as well as servants’ rooms on the second floor. Ten years later, the 1891 census lists a similar number of servants, but the governess has departed as all the children are now grown up. As this was a time when all heating was by open fire and coal and hot water had to be carried, this was a fairly modest staff to run it. There were also extensive gardens, running southwards to Boundary Road and westwards to Chelmsford Road. No gardeners are listed in the census, but it is likely that at least one gardener was employed but lived elsewhere.

Read’s obituary tells us he died “a comparatively poor man”. Certainly, although he retired at least twice but returned to work to top up the coffers, he finally gave up The Chestnuts and moved to a house with only eight bedrooms. The 1901 census return, taken just before his death, finds him widowed and living in Wanstead with three of his daughters, two nurses, a cook and a house parlourmaid. His eldest daughter Mary is now listed as a professional musician – she was to go on to have a successful singing career in the years following her father’s death.

It is sad that Read is scarcely remembered in Walthamstow, despite his years of service and of philanthropy. His grave, in Queen’s Road Cemetery, was resold in the 1970s and is covered with a memorial to the new owners. The Chestnuts was sold to the local authority, and was used for twenty years as a mental hospital – in the terminology of the time a “woman’s lunatic asylum”. Minimal alterations were made for its new use, but these included nets under the first floor landing so as to reduce the risk of any patient throwing herself downstairs. The house has been used for a variety of educational purposes through much of the twentieth century, but is currently lived in by property guardians

The Chestnuts belongs to the people of Waltham Forest, and after multiple false starts, there is still no sign of a plan that will restore this precious survival, currently badly neglected, and ensure it is made accessible to everyone. Just before the pandemic Clio’s Company arranged some school visits, events and an open day. On just one afternoon there were over 400 visitors of all ages. A “to let” sign went up in early 2022. Now, in September, it is still there.

2 pings