We are often told that celebrity is a modern invention that came to birth with the advent of the cinema. Or, pushing it, that Lord Byron, followed in the streets of London by adoring young women clutching copies of “Childe Harold” was the first example. The idea that the first celebrities might have been Londoners of far longer ago, and that some of them might have been women themselves, is probably new.

For the past two years I have been spending many of my waking hours in the company of a long- dead playwright. Aphra Behn’s name is still not as famous as it deserves to be. She began life as the daughter of a Canterbury barber, started her career as a spy in the early years of the Restoration, became the first woman to earn her living as a writer, created and directed nineteen plays as well as poems, novels and translations, and seems to have known everyone in the London of her day. She was never rich, but when she died, aged only forty-eight, she was buried in Westminster Abbey. Aphra Behn wrote for the first generation of actresses, who were as recognisable as she on the streets of a city that was still small enough for its citizens to recognise many of their neighbours by sight.

Then, as now, London was the place where the ambitious came to seek their fortunes – it was where the jobs were, and where a young population either made it or quietly vanished, either returning to the country or dying heartbreakingly early. And the young Aphra, born Johnson, was not the only girl to find her way to London from Canterbury. We don’t know most of their stories. But at least one other found fame of a kind, although her story ended very differently.

Mary Moders was a couple of years younger than Aphra Johnson. She too was part of a modest family – her father was a fiddler, and possibly also a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral. Mary married young, taking as her husband a shoemaker called Thomas Stedman. They had two children together – both died as babies. And after a couple of years, Mary left for Dover, where she married a surgeon called Thomas Day. Evidently she had not gone far enough, as she was soon recognised and, by some accounts, put on trial for bigamy. The next we hear of Mary is in Cologne, where she evidently had a short-lived affair with a much older rich man, who wanted to marry her. But Mary departed for England with the valuable jewellery he had given her as well as several faked letters relating to her imagined inheritance.

Back in London in 1663, Mary took up residence in the Exchange Tavern under the name of Princess van Wolway and claiming to be a German heiress. She became engaged to a young lawyer, John Carleton, who also claimed to be heir to a fortune – in fact he was the nephew of the landlord of the Exchange. After the hastily arranged wedding, it became clear that both were liars. The Carleton parents became involved, and an anonymous letter writer told the story of Mary’s previous marriages – unfortunately for the Carletons they were too mean to pay the fare from Canterbury to London of the only known witness of her previous weddings. So Mary was acquitted, and remained technically married to John Carleton, but he and his parents kept her jewellery and threw her out.

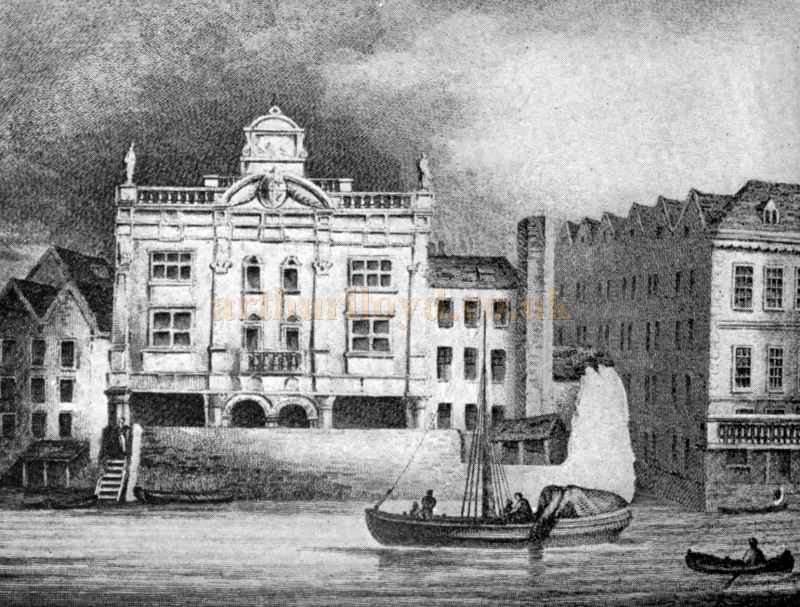

While in prison awaiting trial, Mary had become famous. Samuel Pepys, among many others, visited her, and was impressed by her charm and wit. Pamphlets telling her story sold well, and her admirers were relieved at her acquittal. But she still had a living to earn. A play about her life, “A Witty Combat, or the Female Victor” when into rehearsal at the Duke’s Theatre, and Mary accepted an invitation to appear in it as herself. Pepys recorded having gone to see the show, but was somewhat disappointed. Clearly Mary’s future was not likely to be on the stage. What she seems to have done is to have a series of affairs with affluent older men, stealing money and valuables and then quietly vanishing. Many of the men seem to have kept quiet rather than admitting to having been duped. At least one, however, did complain, and Mary was accused of stealing several items of silver plate. This was then a capital offence, and she was condemned to death, with the sentence being commuted to transportation to Jamaica.

In Jamaica, Mary worked as a prostitute for a few months. But she appears to have persuaded a ship’s captain to take her back to London, where she was able to resume her previous activities, including making at least one more marriage – this time to a rich apothecary in Westminster, whom she soon left. It was not until 1672 that her luck finally ran out. She was again accused to stealing silver items and imprisoned awaiting trial in Newgate, where the turnkey recognised her as the German Princess of the previous decade.

This time there was no escape. Mary Carleton was condemned to death for returning early from transportation. She was hanged at Tyburn in January 1673, making the final speech that was expected from those about to die, admitting to having been motivated by vanity, but hoping for God’s forgiveness. Someone in her life paid for her to have a marked grave at St Michael’s Church, and within weeks an enterprising writer, Francis Kirkham, had cashed in on her death by publishing a pretended autobiography of her: “The Counterfeit Lady Unveiled”, which, along with assorted pamphlets, sold well.

It seems extremely likely that Aphra Behn and Mary Carleton knew of one another. Coming from the same city, from similar backgrounds, there are some distorted similarities between the careers of the two women. Both entered into a London adventure, launching themselves into the ferocious Restoration city that destroyed so many. Both travelled abroad, both worked in the theatre, both attained a measure of fame. Easy to imagine Mary Carleton on a Reality TV show in the present day – and tempting to speculate what worlds a twenty-first century Aphra Behn might inhabit.