A treble love story, music, spectacle, music, dance, stage machinery, knockabout comedy and a gullible old pseudo academic with a pretty daughter, a twenty-foot property telescope and a belief not only in the Man in the Moon but a world in the Moon. A smash hit musical, and so far, so frothy, perhaps, viewed from 2021. It was the last play Aphra Behn completed and had staged in her lifetime – “The Emperor of the Moon” not only attracted the crowds in the uncertain days of 1687, but became a staple for the next half century, guaranteed to get bums on seats in atrocious weather or on a Friday 13th. But there’s more there than froth and spectacle.

This was a world where scholars were discussing the possibility that there was indeed a world in the Moon. The Royal Society had been founded a generation before by a group including what are now famous names including Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, with Prince Rupert of the Rhine presiding. But one of their number, eminent in his day, was one Reverend John Wilkins, who had studied both theology and natural philosophy, and who was to end his career as a Bishop.

Wilkins, born almost certainly at Canons Ashby in Northamptonshire, was the son of Walter Wilkins, a prosperous goldsmith, and Jane Dod, of a local gentry family. Walter died when his son was a small boy, and Jane remarried a Francis Pope, going on to have more children, including another Walter, who was also to become a scientist. John Wilkins was educated at Oxford, where he gained an MA. It was while there that he was able to view the Moon through one of the first telescopes to be set up in this country – the cutting edge technology of its day.

The now visible face of the Moon was a revelation – many serious astronomers believed that they could see not only mountains and seas but cities. There were suggestions that there was a whole civilisation there, waiting to be discovered, and traded with, by the citizens of Earth. In 1620 Ben Jonson staged a Court Masque about the topic. The fact that this was the talking point of its time is demonstrated by a first scene in which a printer, chronicler, factor (marketer) and two heralds agree that this is the latest news. Jonson takes the view that the inhabitants of the Moon are Volatees, or birdmen. The final section of the entertainment, led by the Prince of Wales, is largely given over to flattering King James – always the first concern of any sensible courtier.

In the following years interest in astronomy was intense. There was as yet no formal grouping for this area of study, but not only at Oxford and Cambridge, but in rectories up and down the land there was much thought and observation given to the Moon and the workings of the heavens. Near Preston, the Rev’d Jeremiah Horrocks observed the transit of Venus from his garden. And in his palace north of Cardiff, Francis Godwin, Bishop of Llandaff wrote the first work of science fiction in English, “The Man in the Moon” – a glorious fantasy featuring an adventurer flown to the Moon by wild swans. The book appears to have been a bestseller, and was probably known to Aphra Behn.

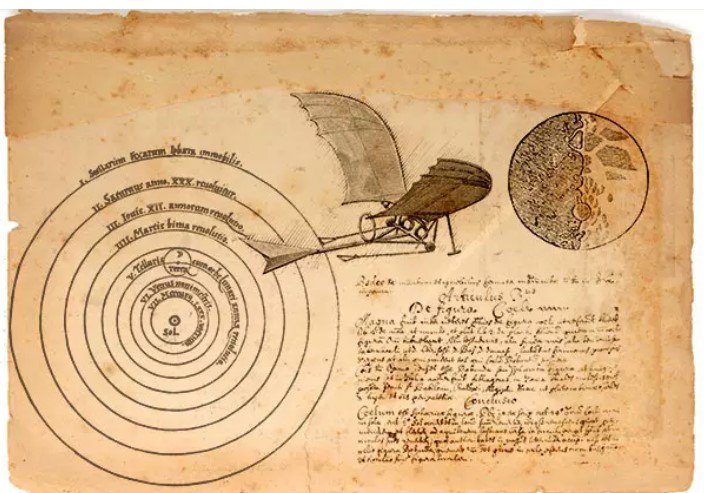

The twenty-four-year-old John Wilkins was writing his own Moon book, “The Discovery of a New World in the Moon” at much the same time. This was, however, a very different work. Wilkins divided his ideas into thirteen serious propositions, about the Moon itself, its nature and the nature of space. One of them being the ringing “That a Plurality of Worlds Does Not Contradict any Principle of Reason or Faith”. He and Robert Hooke tried to build a spaceship in the garden of Wadham College, Oxford – they reckoned they needed a skilled blacksmith and £400 for the project, along with a supply of feathers to cover the clockwork wings. It is not known at what point they accepted that their creation was destined never to leave the ground – or what finally happened to it.

Wilkins was to update his book several times in the next thirty years; he had a successful academic and church career, holding appointments at both Oxford and Cambridge. He married Oliver Cromwell’s sister, and so lost his Cambridge position on the Restoration, but quickly regained the lost ground – John Aubrey thought he was “no great read man, but one of much deep thinking and of a working head”. Wilkins advocated a universal language and was one of those who, in those pre Newton days, believed that gravity was a form of magnetism. He was a founder member of the Royal Society, and spent much of his time in London, notwithstanding his appointment as Bishop of Chester. This was a small circle, and it is likely that he, too, was known to Aphra Behn. Like so many others of his time Wilkins appears to have been killed by the medical treatment he was undergoing; he died in 1671, aged 58, and is buried in St Lawrence Jewry.