Plenty of stories out there to choose from, of course – from the Romans leaving the country in two straight, orderly lines in 410, to the dream of crime and conflict free unity in the Blitz. And a rich selection of people glossed over with layers of storytelling, from the Princes in the Tower to Jack the Ripper. The same turns out to go for local history. Some themes are everywhere: underground tunnels. Lost Roman villas. Visiting monarchs, Elizabeth I or Charles II for preference. And plague pits.

Specifically, at this precise moment, a plague pit claimed to be in Walthamstow. On the face of it, nothing too unlikely about that. St Mary’s, Walthamstow has been a parish church for nearly a thousand years, although little remains of the building that was created in the time of Ralph de Toni, standard bearer of William the Conqueror, in around 1108. In the centuries since, the church has been added to, upgraded, knocked about in wars, locked up, opened up and repeatedly reimagined – it emerged from the Second World War shorn of most of its south aisle. However, it is surrounded by what is now sometimes referred to as “the church campus” – a graveyard as old as the parish, with a former school building dating from 1828, the site of the original vicarage, many times rebuilt, and the almshouses first endowed by Sir George Monoux, the Tudor merchant and Lord Mayor of London who settled locally and who also founded a school and funded extensive rebuilding of the church where his memorial still survives.

The street layout around St Mary’s remains, give or take a few recent incursions by the local authority, much as it has been for several centuries, although many of the names have changed. Orford Road, for example, has skirted what used to be the common land for at least four hundred years, but only acquired its present name in the eighteenth century. And the iconic Ancient House, star of so many photographs and watercolours, itself fifteenth century and the site of an earlier manor house, passed several centuries covered in utilitarian weatherboarding and serving as several shops and a café. The romantic name started to be used after the building was saved from collapse and restored by a local builder.

Another name, less romantic, has a story attached: Vinegar Alley runs along the periphery of the churchyard. Over recent years several claims have appeared on websites that this is because the lane runs alongside a burial site associated with the Great Plague. Some of the sites go on to describe dead bodies being brought in carts from London to Walthamstow in 1665, and the name Vinegar Abbey deriving from attempts to disinfect the area with vinegar. A graphic and memorable story.

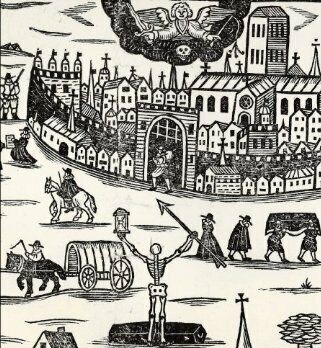

The 1665 plague killed at least 68,000 Londoners, a figure that may well be an underestimate. Serious attempts were made to contain the infection, with houses being placed in quarantine if one inhabitant become ill. The dead were collected at night; bodies were loaded onto carts and, as the epidemic continued, buried with little ceremony in pits on the outskirts of the city. Multiple burials have been located, and sometimes excavated, at Aldgate, Houndsditch and Bishopsgate, among many others. Attempts were evidently made to bury the dead in, or close to, consecrated ground, although this became difficult as the outbreak spread. Daniel Defoe was five years old at the time of the Great Plague. His “Journal of the Plague Year” is a work of imagination, yet he was a Londoner with relatives who survived the epidemic. Some of the records were destroyed in the Great Fire of the following year, but the burial grounds were there for all to see, including the Great Pit described in the book as being located at the edge of the graveyard of St Botolph without Aldgate. When Aldgate Station was created in the 1870s, human remains were discovered, although it remains unclear whether the bones were those of Plague victims. All the evidence, however, is that London plague victims were buried as close as possible to where they died.

In 1665, as in other plague years – about one summer in ten claimed a significant number of victims – towns outside London did their best to avoid infection. However little was known of the exact way the disease was carried, no one was in doubt that it was dangerous to come into contact with a sufferer or their possessions. Elizabeth I had taken refuge from the plague at Windsor one hot summer, and decrees forbade anyone travelling from London to Windsor; transgressors were hanged without trial. And, famously, at Eyam in Derbyshire in 1665, the community agreed to isolate themselves to protect others once the infection arrived in their midst in a parcel of patterns sent from London.

Between those extremes, people did their best. Walthamstow was a small place, a series of hamlets connected by lanes. In the Tudor period only around 100 people lived there; most worked on the land – there were rich meadows, hop fields and at least one mill. By 1679, a few years after the plague, there were 189 buildings, so it is realistic to imagine a population of perhaps 500. We do not know with certainty whether the plague reached there in 1665 – there is a story that local people stood guard at the ferry so as to deny entry to London refugees, but there would of course have been nothing to stop the determined and the desperate from making their way across the marshes. It is true that vinegar was used for disinfecting purposes at this time, and the claim is that quantities of it were used to ward off infection from the corpses thrown into a nearby mass burial site. Sadly for that theory, the name Vinegar Alley appears to date only from the late eighteenth century. At that time Beulah Road and the surrounding area were home to the main industrial and commercial premises for Walthamstow, and these included a leatherworker whose trade would certainly have included the use of much vinegar.

There is also a claim that errant plague pit was actually some distance away, and was disturbed at the time of the creation of the Chingford Line in 1870. The land to make the line was part of the Berryfields, some of which was inclosed and sold to the railway company by the Vestry (the predecessor to the Council). It was indeed common at this time for work on the new railway lines to unearth burials; the remains were routinely reinterred. There does not, however, appear to be any evidence for this. There is a blue plaque on the former Sorting Office recording that the playground opposite was once part of the Berryfields. But nothing about bones.

It is of course impossible to be sure. Some myths and legends have their roots in historical fact. Only a couple of years ago archaeologists uncovered the remains of a Roman settlement only metres from St Mary’s church: no one appears to have known. And sometimes the unfeasibly unlikely happens: Richard III’s remains being dug up intact in a Leicester carpark would be unbelievable if it had not happened. Far less likely than a plague pit in an old churchyard.