Watercress sandwiches aren’t really a thing now. Gone the way of cucumber with the crusts cut off, and unlikely to be included in the riverside picnic of any modern day Ratty along with the cold meats and French rolls. No watercress for sale in the market either; just bags in supermarket salad aisles alongside the more favoured rocket.

Walthamstow was once famous for its watercress. And looking at the 1822 Coe map of the area, it is easy to see why – the minutely recorded expanses of meadow are criss crossed with ponds, streams and blue shading and drawn in tufts of grass for the more notably damp meadows. Some of the many local market gardeners had a watercress bed or two, and gathered and sold the cresses commercially. And before the days of compulsory education, children would buy or gather watercress to sell at street corners. The original map is in Vestry House Museum, and there is more information about the map on www.queensroadstories.org

In Henry Mayhew’s 1851 “London Labour and the London Poor”, an eight-year old interviewee was earning her own living by arriving at Farringdon Market at four in the morning, buying a supply of cress which she then tied into bunches and sold to office workers, earning a few pence profit a day. This child had a home and family, but was dressed in a thin cotton dress and shawl in the depth of winter and subsisting on a cup of tea and two slices of bread and butter, twice a day, with a hot meal once a week. Mayhew’s campaigning work, and in particular this child and her poverty, became famous. Her down to earth character and practicality come over strongly – a contrast to images such as the painting of a watercress girl by Johann Zoffany, in which the girl and her vulnerability are touching, not disturbing – poverty with a pearly complexion and in a clean dress.

We do not know anything more of Mayhew’s interviewee. But there were many small girls with lives not unlike hers. In Walthamstow around that time, Emily Clark and her grandmother were living in Markhouse Lane. The grandmother was officially a pauper; by this date the elderly were often permitted to come and go from the workhouse depending on the time of year. The two of them appear to have kept going by selling ginger beer and watercress, probably from a barrow, possibly to the commuters coming and going from Lea Bridge Station, still the only railway in the area.

Before the days of trains, many street sellers would walk from Walthamstow and Leyton to London’s more lucrative streets along the Black Path – this was a route used by drovers on their way to the London markets with everything from cows to geese. And even after the trains came, the path was still much used by the many who could not afford the fare. This was long before the days of cheap workmen’s tickets, and rail travel was only for the moderately prosperous. And this was still a generation before education for all children became compulsory, even in theory. And in Walthamstow, when the newly created school board counted how many children needed school places, there was a shortfall of at least 1,000. They did their best, but even once there was a school place available, many children, especially girls, were kept at home. Some were doing the washing, some looking after younger siblings – some out selling flowers or watercress.

Much later, after the Boer War, one young widow, a Mrs Dyson, left with small children, fought to keep her family out of the workhouse. She went out cleaning steps, taking the baby with her. She also gathered and sold watercress, standing on the side of the road offering bunches to passers-by, sometimes with her skirt soaked to the knees as she had come directly from gathering cress. In the evenings she was doing piece-work for a local factory, and sewing. They got by – she too lived mostly on tea and bread, in this generation with margarine.

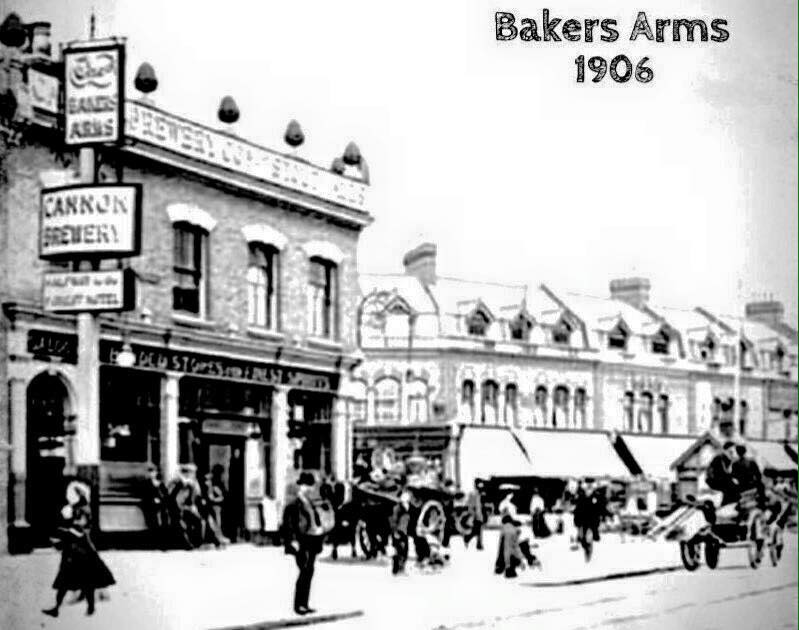

But the days of the watercress beds were numbered. Along with the railways came exponential growth. Between the 1860s and 1911, the population of Walthamstow doubled every ten years. The damp meadows were built on – when young Arthur Spencer and his family moved to Longfellow Road, his first memory of their newly built house was the men coming to fill in the watercress beds. The ponds were covered over, and the streams culverted. In the early 1900s most people used their gardens to grow flowers or vegetables – the neglected ones reverted to the damp meadow they had always been. But in wet weather, the water that had once ended up in streams and ponds now ran down roads and into houses – the infrastructure could not cope, several decades before the fashion for decking and astroturf arrived.

The culverted streams are still there – near the site of Arthur Spencer’s old home you can hear the running water, especially after heavy rain. But such watercress as is sold locally is bought in from elsewhere.